If you fall into a certain age group — and I’m going to go out on a limb here and guess that the age group is between the ages of 25 and 40 — chances are that you can quote whole passages of dialog verbatim from the movie The Princess Bride.

Admit it. If you’re in that age group and I say the name Inigo Montoya, you will immediately respond, “My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.” (Extra points if you can mimic Mandy Patinkin’s soft spoken yet intense faux Italian accent.) And if I say the word “Inconceivable,” you will parry by saying, “I do not think that word means what you think it means.”

Here’s my own confession: I’m not in that age group.

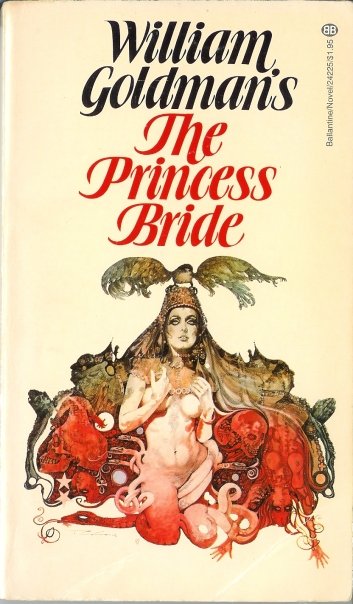

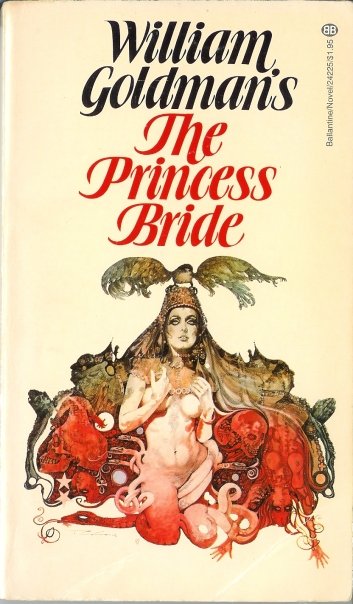

When I discovered The Princess Bride, there wasn’t a movie version of it yet. The book that the film was later based on wasn’t even especially popular and had been mostly panned by critics. I first came across it in an extremely difficult-to-find paperback edition from Ballantine Books, an edition so difficult to find that I saw it at precisely one drugstore newsstand — and this was at a point in my life when I practically lived in bookstores and drugstore newsstands looking for new paperbacks to read. The cover was an oddly inappropriate painting of a sultry, mostly naked woman who looked a bit like Kim Novak without her signature blonde hair.

“This is my favorite book in all the world, though I have never read it.”

While she was certainly an eye-catching cover girl, what mainly interested me about the book was that it was written by William Goldman, a writer who had already endeared himself to me by writing the unputdownable thriller Marathon Man, which was turned (with Goldman’s help) into an excellent movie starring Dustin Hoffman and Laurence Olivier. And I had been aware of Goldman since even before Marathon Man, because he had made his reputation in the 1960s by writing the novel Boys and Girls Together, which tended to get passed around classrooms because, by the standards of the time, it had titillating sex scenes in it. (Another confession: I have never read Boys and Girls Together, though I have a used paperback edition on my shelf and the e-book version on my Nook. I still plan to read it someday.)

Goldman was a writer who intrigued me because he wrote fiction that was both intelligent and utterly gripping, two qualities — intelligence and grippingness — that aren’t easy to squeeze into a book at the same time, at least judging by all the mindless thrillers that you can find on bestseller lists to this day. I had never heard of The Princess Bride, which also intrigued me, because I thought I was aware of at least the titles of all the books Goldman had written up until that time, even if I hadn’t read most of them.

Naturally, I snatched a copy — possibly the only copy — off the shelf, bought it, and took it home.

I started reading it as soon as I got back to my bedroom, because I didn’t want to lose the excitement I felt at discovering it. And, as with Marathon Man, I couldn’t put it down. But it was better than Marathon Man. It was possibly the most extraordinary book I’d ever read. Goldman did things in it that I’d never seen a writer do and combined elements in the story that I’d never seen a writer combine, mixing satire with breathtaking action while maintaining a mood of both humor and gut-wrenching pathos, all in what amounted to an epic fantasy. I put the book down wrung dry emotionally, a tear in my eye and a sad smile on my lips. I still remember the book’s closing lines, which I’ll quote for you later. (And if you only know The Princess Bride from the movie, you won’t recognize them.)

Eventually the Del Rey Books division of Ballantine, which had been established strictly for publishing science fiction and fantasy, recognized that it had this gem of a novel in its corporate backlist and realized that with the craze (which had actually been started by the editors at Del Rey when they published Terry Brooks’ Sword of Shannara) for books that essentially cloned the Lord of the Rings, they might be able to repackage The Princess Bride in such a way that they could convince Tolkien fans to buy it. This ploy worked surprisingly well and the book finally became the bestseller it had always deserved to be. I was happy for Goldman, because by then I had read several more books by him and knew that The Princess Bride was no fluke. Goldman was a smart and entertaining writer, though even in the masterful oeuvre he had compiled by the early 1980s, The Princess Bride stood out as the most extraordinary thing he had ever written (and will probably remain so, given that he hasn’t published a novel since 1987).

Then, in 1986 or 1987, a film version of The Princess Bride was announced. Goldman, who had long maintained a highly successful second career as a screenwriter, would write the script and Rob Reiner, who had shown great promise with the adolescent bonding movie Stand by Me (based on Stephen King’s novella “The Body”), would direct it. Although I fell into the camp that felt that The Princess Bride was essentially unfilmable, that much of what made it a great novel would be lost in the translation to screen, I was guardedly hopeful about it, especially with Goldman himself involved in the project. Maybe they could indeed make a great film out of it, a film as great as the book that inspired it. And, though the movie was slow to catch on, it did eventually become a cult sensation with a generation of young moviegoers, beloved for its quirky characters and imminently quotable dialog.

God only knows why. I’m sorry, people, especially if you love the movie, but the naysayers were right. The book was unfilmable. Even with Goldman as screenwriter, it lost most of what made the book so wonderful.

Maybe I should stop at this point and explain what the original book was about. If you know it only through the film, you’re not going to recognize most of it.

It was about a middle-aged screenwriter (named “William Goldman” and referred to throughout the book in the first person, but really a thoroughly fictionalized version of the William Goldman who was writing the book) who, with a failing marriage and thoroughly alienated son, had lost all joy in life and all sense of wonder in the things that had thrilled him when he was young, especially great adventure novels. It was about his attempt to regain these feelings by returning to a book that his father had read to him when he was an adolescent, The Princess Bride by the great Florinese writer S. Morgenstern. (His “father,” also a fictional character, was an immigrant from the imaginary country of Florin.) Morgenstern’s The Princess Bride had been the book that awakened the fictional Goldman’s own sense of wonder and he wanted to share it with his own son as a bonding experience, something that would not only save his marriage and his relationship with his son but that would vicariously reignite his own joy in life.

Yet when he read The Princess Bride himself — up until then it had only been read to him by his father — he discovered that the book had not been what he thought it was, that in fact it had been intended as satire, filled with barbed, very dry jokes aimed, in many cases quite tediously, at the ruling families of Florin, and the exciting adventure novel that he remembered his father reading to him was buried under page after page of cynical social commentary that his father had wisely left out. The fictional William Goldman talked his editor into letting him revise the book, which was long out of print, and publish a “good parts” version, with Goldman’s own annotations explaining (often humorously) why he had excised large amounts of text at several points in the narrative. The resulting abridgment was an absolute wonder, every bit as thrilling to an adult reader as it must have been to “Goldman” as a child. Yet at the same time you could tell from Goldman’s annotations that the “original” book, as the imaginary S. Morgenstern had written it, had been larded with exactly the kind of adult cynicism that Goldman was trying to escape from by sharing the book with his own child.

The fictional Goldman never did repair his relationship with his son and in editing the book he discovered that the original ending his father had pretended to read to him — “And they lived happily ever after” — was not how the book really ended. In fact, it ended with the heroes being defeated, true love failing to triumph, and the villains getting their way as villains so often do in real life. And despite having edited it into the thrilling book that he had always believed it to be, the fictional Goldman ended the book in a deeper depression than he had begun it in, closing with some of the saddest lines in all of popular literature:

“I’m not trying to make this a downer, understand. I mean, I really do think that love is the best thing in the world, except for cough drops. But I also have to say, for the umpty-umpth time, that life isn’t fair. It’s just fairer than death, that’s all.”

I was young when I read the book, but not so young that I couldn’t feel my childlike sense of wonder already beginning to ebb (and one of these days I still expect it to go away completely). Goldman’s book captured that feeling perfectly, with its brilliant contrast between the genuine, almost hyperbolically thrilling novel that lay buried underneath Morgenstern’s crushing adult cynicism, the same cynicism that was already beginning to crush the soul of the fictional adult Goldman — and maybe, in a somewhat less hyperbolic way, the soul of the real William Goldman too.

The movie went for the thrilling hyperbole of the book as the fictional Goldman had known it as a child, but it was filmed on a fairly meager budget and was unable to find a cinematic equivalent of that hyperbole, what Goldman’s father had described as ““Fencing. Fighting. Torture. Poison. True love. Hate. Revenge. Giants. Hunters. Bad men. Good men. Beautifulest ladies. Snakes. Spiders. Beasts of all natures and descriptions. Pain. Death. Brave men. Coward men. Strongest men. Chases. Escapes. Lies. Truths. Passion. Miracles.” All of that, as over the top as it sounds, really was in the book and it was as exciting as it sounds like it ought to be, but the movie needed more visual spark and passion to pull it off. Some critics misguidedly praised the movie for playing against expectations by pulling back on the spectacle, but that was a necessity that never really became a virtue. If ever a film needed to be spectacular to stay true to the nature of a book, it was this one. It needed a cinematic equivalent of the hyperbole of the book and it couldn’t afford to create one. Maybe if you were a certain age when you saw the film and hadn’t lost your childlike sense of wonder yet, you found a bit of that in the movie and I envy you that. I was too old by the time it came out and for me it was completely missing.

But where the movie completely failed was in not capturing or even attempting to capture Goldman’s heartbreaking frame story, substituting the lame gimmick of having Fred Savage (appropriately enough of The Wonder Years) read the novel by an immigrant grandfather played by Peter Falk). The more adult portion of the framing story, though, with its failing marriage and sense of a man desperately trying to escape the depression that adulthood was sucking him into, was totally gone and I missed it sorely.

For me, The Princess Bride is about the loss of sense of wonder in adults and one man’s successful attempt to convey that sense of wonder to adult readers while at the same time dismally failing to recapture it in himself. The novel of The Princess Bride is heartbreaking and cynical, immensely thrilling and comical, all at the same time, which is something I’m not sure I’ve ever seen another book manage to be and something the movie absolutely wasn’t. And I’m sad that an entire generation knows it only as that clever, quotable little film that completely lacked the heartbreak and ambition of the novel.

Oh, I’m quite happy that you can quote dialog from it and that some of those lines, all of which were in the book as well, have found their way onto everything from t-shirts to coffee mugs, but if you’ve never read the book do me a favor and go to a bookstore or to Amazon.com right now and order a copy. I’ll thank you, William Goldman (who is now 82 and, based on a video I saw of him the other day, still sharp as a tack) will thank you and S. Morgenstern will thank you.

And, as the fictional William Goldman says at the end of the book’s prologue, “What you do with it will be of more than passing interest to us all.”