Geekomancy 101

Fantasy means magic. Sometimes. A lot of the time, honestly. And from Jack Vance and Ursula K. LeGuin, J.K. Rowling to Brandon Sanderson, nearly all fantasy worlds have magic systems. Some are vague, arcane (Lord of the Rings, The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms, Pretty Much All Mythology Ever), and some are well-stratified, almost a science in and of themselves.

On the ‘More Explanation!’ side of the equation is Brandon Sanderson, who is famous for many reasons, one of which being his excellently-drawn magic systems. Brandon has rules about magic. No, not rules, Laws. Sanderson’s first law of magic states:

“An author’s ability to solve conflict with magic is DIRECTLY PROPORTIONAL to how well the reader understands said magic.” (

http://www.brandonsanderson.com/article/40/Sandersons-First-Law).

So when we talk magic, we’re getting into the Big Stuff. The stuff that, well, separates the fantasy from the everything else. I’m a gamer, and so like many gamers who were once twelve, I’ve had my phase of obsessively memorizing statistics, characteristics, and every other little tiny bit of information there was to be had about games I was playing as a pre-teen and young teen. I had to know how everything worked, had to know the text of every card so I could run my brain through every possibility.

I’m not twelve anymore. I don’t obsess about details as much as I used to, don’t exhaustively read RPG setting books anymore to memorize an entire fictional world’s atlas.

I do the work I need to do in order to tell the story I want to tell.

And when it came to making up the magic system in Geekomancy, a magic of fandom and gaming, I had to find the balance between twelve-year-old me who wanted to define everything and the me who was more focused on telling a fun story than on obsessively detailing an entire magic system down to durations in rounds and effect radii in meters.

The magic of Geekomancy is, like many magic systems (a la

Mage: the Ascension,

Unknown Armies,

Harry Potter, the

Dresden Files, etc.), about passion, belief, and investment of will into action.

But stratifying rules was not my objective with the style of Geekomancy. My objective was to ask the question “If geeks had magic, what would it be?” and then answer it in as entertaining and thoughtful way as I possibly could.

To answer that question, I took what I saw as the cores of geekdom – enthusiasm for and identification with the properties you love, and a strong thread of collector-itis.

With that, I ended up with three main types of Geekomancy:

- Genre emulation – Some Geekomancers can immerse themselves in a text/narrative/cultural property they geek out over – and when they do, that passion creates a magical charge. The Geekomancer can then draw on that charge to do cool magical stuff that is associated with the text/narrative/cultural property in question.

Example: My protagonist, Ree Reyes, is a big Star Wars fan. In Celebromancy, she watches Star Wars (aka Episode IV: A New Hope), and then uses that charge to use a Jedi mind trick, Force stealth, telekinesis, and force speed.

- Props – a Geekomancer can take a prop or artifact from a beloved property and use that prop to do what it did in the property – use a Star Trek phaser to blast, Wonder Woman’s bracelets to deflect bullets, and so on. Each prop has a nostalgia battery, and being magic runs that battery down. When the battery is empty, it has to re-charge by absorbing a portion of the collective nostalgia of every person who’s ever thought ‘how cool are phasers’ or cheered a Star Trek officer on as they fire away.

Example: Ree has a cheap Deep Space Nine phaser prop – because it’s cheap, and a widely-available model, it has a smaller nostalgia battery, and is less powerful overall. If she got her hands on an actual phaser prop used on the show, it’d be substantially more powerful – it’d do more damage and it’d be able to be used for much longer.

- Expendables – The last type of Geekomancy is the down-and-dirtiest. A Geekomancer can take an object associated with a geek culture property, and destroy it for a one-shot specific effect. This method is used for artifacts that don’t count as props – cards from CCGs or comics issues instead of phasers and lightsabers and jet boots.

Example: Uncle Joe is a regular at Grognard’s. He’s a CCG specialist, with an extensive collection. Uncle Joe can pull out a fireball card, tear it, and direct the fireball anywhere. Or he can tear up a creature card and summon the creature to fight for him. But every time he does it, the card is ruined, diminishing his meticulously organized collection.

Each type of Geekomancy can be used in a number of ways, that Ree learns are really mostly dependent on the magician. There’s an infinite number of ways to be a Geek, and each Geekomancer has their own relationship to fandom, and therefore, to their magic. The other magic systems in the world are similar, reflecting the worldview of each magician. Doing this allows for variation and consistency to work in harmony for flexible storytelling that’s easy enough to follow that, hopefully, readers won’t feel like the magic is all-hand-waving and no coherence.

Each book, Ree’s understanding of Geekomancy will grow, and she’ll share that with readers. My objective with the Ree Reyes series is to show ways that geeks might try to shape the world around them, to reflect how our fandoms inspire us, educate us, and shape our view of the world. That and to show readers as good a time as I can along the way.

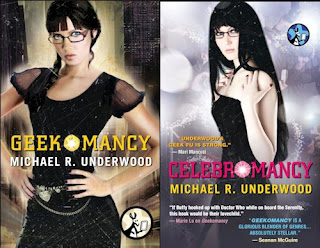

Michael R. Underwood is the author of GEEKOMANCY, CELEBROMANCY, and the forthcoming YOUNGER GODS (2014). By day, he's the North American Sales & Marketing Manager for Angry Robot Books. Mike grew up devouring stories in all forms, from comics to video games, tabletop RPGs, movies, and books. Always books.

Mike lives in Baltimore with his girlfriend, an ever-growing library, and a super-team of dinosaur figurines & stuffed animals. In his rapidly-vanishing free time, he studies historical martial arts and makes homemade pizza.

Website ~ Facebook ~ Twitter @MikeRUnderwood